Why do we notate juggling?

Table of Contents

Introduction⌗

What are the motivations, functions and reasons for notating at all? Can’t we just film our tricks?

Notation can be used to record, analyze, generate, compose, communicate, and progress an art form like juggling.

In this article I explain what notation is and why it is valuable to juggling.

What is notation⌗

Notation systems consist of tokens and rules that describe abstractions. They help us understand reality and are therefor a vital part of revolutionary progress in all kinds of complex systems.1 Notation is commonly used in areas like music, math, chemistry, cartography and of course writing, but even speech could be seen as a notation system.2

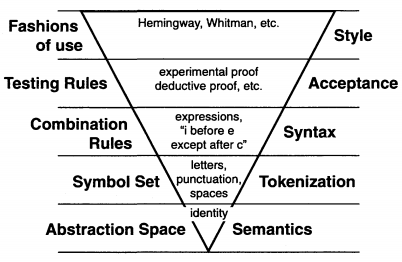

In “How could the notation be the limitation?”, Jeffrey G. Long1 identifies the different levels of a notation system (fig. 1,) , and I will summarize those levels here.

- At the bottom level there are the abstractions that make up the systems. New abstractions bring new concepts into existence, and these concepts define how the users of a system understand reality. For example, the musical note

Cdid not exist before it was named, yet today probably most musicians think of a melody in terms of notes on a scale. Similarly, speakers of different languages may categorize and understand colors differently.3 - The second level is the tokenization of this abstraction. It must be made tangible through words or symbols in some medium in order to communicate or operate upon them. Typically this tokenization comes with a set of symbols that are to be used in a notation system.

- Knowing the symbols alone is not enough, level 3 is about the rules of how these symbols are combined to form meaning.

- Not all valid combinations of tokens are equally meaningful, in level 4 we can discuss how to test if a combination makes sense before we accept it as part of reality.

- And finally, level 5 is about different valid ways of expressing something with style or fashions of use.

Let me give an example of each level using the IMBO notation system for juggling body tricks:

- Level 1 describes the topological juggler model, and the concept that objects can go through one of 5 holes.

- There are different tokenizations for this abstraction, among which one graphical and one text based. Let’s use the text version for the rest of this example, which uses the symbols

/ \ H M L ~. - The rules of the system explain for example that a path should go through a multiple of 2 holes, i.e. never 1 or 3.

- Both

L/M~H~HM\LandL/HMM~H~\Lare valid patterns, but the first is relatively easy to execute and the second is probably impossible with a toss. - Different jugglers could specialize in the use of a different subset of the possible patterns.

Not all new notation systems need a new abstraction system, for example Roman and Arabic numerals use the same abstractions but the tokenization of the Arabic system allowed for a deeper understanding of the abstractions. However, the most revolutionary notational systems originate from new abstractions.1

Notating juggling⌗

Over 20 unique notation systems for juggling have been identified that were developed over the last 40 years. Considering how much of a niche juggling is, I think this is quite a lot. Why would notating juggling be so popular?

A good friend of mine theorizes that it’s simply because many jugglers identify as “nerds” or have “autism-like characteristics”, who enjoy patterns and structures like those described in notational systems. However, even if it were true that these characteristics are overrepresented in the juggling community, one could argue that it’s the inherent patterns and structures of juggling that is drawing people with interests in those to juggling, rather than those patterns being discovered and notated because by happenstance there are more pattern oriented people among jugglers.

It is not up to me to tell you if juggling is inherently more about patterns and structures than other artistic disciplines, or even if patterns and structures are a requirement for notation. What I can do, is talk about the successes that notation has had within juggling and other performing arts.

The value of siteswaps⌗

Siteswaps and their many extensions can be considered to be by far the most influential juggling notation system. On the Gandini Siteswap DVD its inventors and early adopters describe in detail how infinitely many tricks were discovered or generated thanks to the system. It is hard to imagine for me that there was a point in time, not very long ago, where a simple trick like 441 had not yet been discovered, because the rules of how juggling balls and beats interact had not yet been expressed in a notation system.

Notable juggling companies have explained how their choreographies are created using siteswaps, including Gandini4, Les Objets Volants5, Vincent de Lavenère6, Tall Tales7, and many more. Composing with siteswaps can be incredibly valuable especially when choreographing multiple jugglers, aligning throw heights and rhythms with music scores or working with differently colored props that need to appear in specific configurations.

Other than just creating new tricks, siteswaps have also given jugglers tools to practice and break down juggling patterns. For example in order to improve their 5 ball cascade, jugglers often practice the siteswaps 552 or 5551.

Siteswaps are easy to communicate. As a trick only consists of a few digits you can print out hundreds of tricks on a single sheet of paper. They are also relatively easy to learn for an experienced juggler, often an expert siteswap juggler can correctly juggle a siteswap only a few seconds after being first presented to it.

It is not very hard to simulate siteswap juggling, which is why there have been a lot of siteswap based juggling simulation applications. Some well known examples are Juggling Lab and JoePass!.

When analyzing juggling tricks it can be useful to work out the siteswap of the trick, even if the trick itself may not have been constructed with that in mind. Understanding the siteswap breaks down one layer of the pattern and allows you in a way to isolate the other layers which helps the understanding of them. Juggling can be fairly complex, and seeing a trick may not be nearly enough to understand what goes on.8

Siteswaps only describe a very specific feature of juggling, leaving features such as the “spacing” completely untouched. I imagine it could be revolutionary to juggling if all the values mentioned here became easily available to the “spacing” of juggling too, for example through the use of a new notation system.

Dance notation has existed in some form or another at least 600 years9, music notation well over 2000 years10. In the short 41 years that jugglers have used siteswaps they have already revolutionized how we think about juggling. It’s exciting to think about what notation might do for us in the next 2000 years!

Mediums of notation⌗

Abstractions can be expressed in different mediums. For example, the musical note that is written in text as C4 can be written as a note on a score in modern staff notation, it can be spoken out loud (often called “middle C”), it can be communicated digitally over the midi protocol with the value 60. The different mediums are used in different settings and the mediums have their own strengths and weaknesses, which resulted in abstractions that exist in one medium but not another. For example, in solfège which is a a spoken out loud notation for music, all pitches are relative, not absolute. This concept does not exist in modern staff notation. And in the midi protocol there is always a “velocity” value tied to a note, which describes as how hard a note is played. There is no way to directly translate this velocity value to modern staff notation either.

The purposes of a notation system can hugely influence which medium is most suitable. For example, if I want to have a system for composing long sequences of juggling, I’d want a system in which it is easy to get an overview right away. From looking at a page of sheet music I can quickly tell what the dynamics of the piece are, where the repetitions take place, and if someone where to perform a part of the piece I can probably quickly find it on the page. However, a long string of siteswaps is much harder to read as it is visually homogenous. I need to look closely at the numbers to see what they mean and I have very little overview.

I’m interested in notation for digital communication between people. This is easiest with text based notation, as this can be written in any text editor and sent through most messaging services. However, a downside of this is that as more and more information needs to be used to explain a throw, more and more characters might need to be used. This could make it harder to understand the trick at a glance.

In a graphical system it might be easier to combine multiple layers in a way that takes up less space and is easier to read. For example a single music note on a score can express both its pitch and its length. A single symbol in labanotation can denote a movement’s direction, it’s level, it’s duration, and the body part performing the movement. But a graphical system can be more difficult to write and edit without specialized tools, especially digitally. And learning to read it could take more practice and instruction.

As we add more and more layers of “descriptive dimensions”11 we get closer to actual recreations of what we were notating in the first place. For example, a video is able to capture most qualities of juggling very accurately. But as we approach this near perfect description, we also loose the benefits of the abstractions themselves such as understanding and analyzing through simplification, and being able to express the abstractions using various mediums. This makes it obvious to me that the medium with the ability to describe the most dimensions is not necessarily the best option.

What is the trick⌗

In the article “What is the Dance?"12, Judy Van Zile talks about how a piece does not equal a performance or staging of that piece. In music, a composer may refer to the written version of their music as “the work”, and performances of the work as interpretations of it. A playwright creates a script, a director might create a staging of a piece based on that script, but perhaps only the script itself can be seen as “the play”, and the staging only as an individual rendition of it. If a choreographer does not write down a dance score, then what is the dance? Is it the opening night performance by the original cast? Is a video a true recording of a piece even if it may accidentally include some mistakes of the dancers, or is it only a recording of a performance of a piece?

I think these questions are very interesting, and similarly I ask myself: What is the juggling trick? I feel like most jugglers have an inherent sense of what features make up a juggling trick. When I teach someone how to juggle a 3 ball “cascade”, they need to throw and catch the balls in a certain order but they don’t need to copy my exact rhythm or body posture before we both agree that they too are juggling the “cascade”. Sometimes the features can be a bit more vague and we can argue if juggling moves are new tricks or mere stylistic variations on existing tricks. For example, are there 53 unique juggling tricks in this video, or is there only 1?

Juggling notation can probably help with these questions. If someone suggests that a trick is siteswap 441 jugglers can understand which elements are central to the trick and which are not, they don’t have to make their own deductions from someone’s demonstration. Juggling notations might also stretch our current understanding of what a trick is. For example, Harmonic Throws allows one to note down the movement of the legs even when the juggling does not go through them. I would argue that those movements are dance moves layered on top of juggling tricks, but perhaps the line between dance and juggling will be blurred so much that they can not be seen as separate entities in the future thanks to the notation systems that combine them.

Quotes about notation⌗

If other people say things, they must be true. Or not, who knows. But here follows a small collection of quotes about notation which confirm my belief that notation is valuable.

“Each new notational system, or each new generation of an existing notational system, brings us a clearer understanding of the nature of reality…” - Jeffrey G. Long11

“Notational systems are to our intellectual lives like water is to a fish: they surround us, we swim in them, they support us, and perhaps because they are so ubiquitous we are generally unconscious of them.” … “I have come to believe that much of what confuses us arises from how we look at things. Perception is an active and learned process that can be improved in many ways. We can greatly improve our effectiveness if we better understand the ways we manage our perception, how literacy in a notation changes our perception, and the structure of the many notational revolutions that have occurred in humanity’s very brief history.” - Jeffrey G. Long2

“By relieving the brain of all unnecessary work, a good notation sets it free to concentrate on more advanced problems, and in effect increases the mental power of the race.” - Alfred North Whitehead13

“It is, therefore, this process of production and recognition of symbols, codes, patterns, signs, or combinations of signs that will show itself to be at the base of a process of modelization of complexity by an intelligence.” - Jean-Louis Le Moigne

“It takes more effort (more words, gestures, whatever) to try to express ideas for which there are no tokens. Likewise it takes more effort (more words, gestures, whatever) to try to express any idea with precision and clarity. This increasing difficulty is perceived as a “complexity barrier”.” … “As Thomas Kuhn noted in his classic study of scientific revolutions, often a “period of crisis” will precede a new paradigm in science. Often (but certainly not always) the new paradigm will utilize and require (and be permitted by) a new notation: the infinitessimal calculus in the case of Newton, non-Euclidean geometries in the case of Einstein. This “period of crisis” indicates that a complexity barrier has been reached.” - Jeffrey G. Long14

Olson & Astington (1990) suggest that language literacy, with its focus on precisely what was said, is related to an increased understanding of subjectivity, or precisely what was meant. People who do not learn to read and write at higher levels have difficulties distinguishing between what is said and what is meant and consequently have trouble understanding complex uses of language, such as certain forms of figurative speech (Astington et al., 1988). In the domain of music, the availability of a visual notational system appears to support the understanding of complex and abstract forms, such as sonata form, and to enable the use of musical devices such as inversion and retrogression (Sloboda, 1985). Finally, investigators in the geographic sciences find that understanding the symbolic codes of maps increases one’s ability to recognize and arrive at specific locations. Maps reduce the complexity of navigation by organising spatial information in systematic ways (Gregg and Leinhardt, 1994). - Edward C Warburton15

Hey, you made it to the bottom of the article! You must really be into notation. Well, as a small bonus to you I’ll leave you with a link to more anecdotes about how notation affect thought.

Thank you for reading and goodbye.

References⌗

-

Long, J. G. (1999). How could the notation be the limitation?. ↩︎

-

Long, J. G. (1996). A Study of Notation: Introduction. Notational Engineering Laboratory. https://web.archive.org/web/20040527234214/http://www.cs.vu.nl/%7Emmc/tbr/content_pages/repository/nel/intro.html ↩︎

-

Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A. R., & Boroditsky, L. (2007). Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(19), 7780–7785. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701644104 ↩︎

-

Wilson, T. J. M. & Gandini Press. (2016). Juggling Trajectories. Amsterdam University Press. ↩︎

-

http://www.lesobjetsvolants.com/index.php?page=contrepoint ↩︎

-

Bellocq, E., Guy, J. M., de Lavenère, V., Rioufol, E., & de Lavenère, V. (2004). Le chant des balles. Entretemps. ↩︎

-

Tall Tales Company. (2022). Turning the Cube. Tall Tales Company and Zirkus | Wissenschaft. ↩︎

-

B. Beever. (2000). [Siteswap Ben’s Guide to Juggling Patterns]Guide to Juggling Patterns ↩︎

-

Guest, A. H. (2014). Choreographics: A comparison of dance notation systems from the fifteenth century to the present. Routledge. ↩︎

-

Strayer, H. R. (2013). From neumes to notes: The evolution of music notation. ↩︎

-

Long, J. G. (1996). A Study of Notation: The Foundations of Notation. Notational Engineering Laboratory. https://web.archive.org/web/20040717212502/http://www.cs.vu.nl/~mmc/tbr/content_pages/repository/nel/con3.html ↩︎

-

Van Zile, J. (1985). What is the Dance? Implications for dance notation. Dance Research Journal, 17(2), 41-47. ↩︎

-

Alfred North Whitehead. (1948). An Introduction to Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ↩︎

-

Long, J. G. (1996). A Study of Notation: Notational Evolution and Revolution. Notational Engineering Laboratory. https://web.archive.org/web/20040717213845/http://www.cs.vu.nl/~mmc/tbr/content_pages/repository/nel/con5.html ↩︎

-

Warburton, E. C. (2000). The dance on paper: The effect of notation-use on learning and development in dance. Research in Dance Education, 1(2), 193-213. ↩︎